The future of the electronic voting machines in Brazil depends on the 2022 elections’ results

On October 2nd, over 123 million Brazilians went to the station polls throughout the country and overseas to choose who is going to be their leader for the next four years. Later in this month, they will return for a presidential runoff after neither of the leading candidates managed to secure enough support to win the election outright.

The two candidates running for the presidency, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (commonly known as Lula) of the left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) and the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro of the conservative Liberal Party (PL) have both been given a second chance to rule. Lula, the most popular president in Brazil’s recent history has already served two terms between 2003 and 2010, returns after a major scandal – imprisonment on corruption charges (though later annulled) – with the narrative that he has what it takes to bring the country back on track as one of the world’s leading economies. Bolsonaro, on the other hand, tries to maintain power even through historical controversial decisions, based on his conservative/nationalist views, such as relaxation of gun ownership laws, disdain for human rights and his management of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has killed more than 680 thousand people in the country.

Lula and Bolsonaro represent starkly different visions for the nation’s future and this is represented as well in their trust of the current voting system. While an overwhelming majority of electors in Brazil of three of the main candidates for the presidency in the first term said that they trust the electronic voting system (Lula, 86%; Simone Tebet and Ciro Gomes, 75%), over 74% of Bolsonaro’s supporters say otherwise in the latest Atlas Institute research poll.

Although the citizens’ top concerns may be the economy, which has been in recession since 2014 with ever increasing prices, and social issues, such as Education and public health, there are other major issues at stake, among them, the future of the electronic voting system and even the democratic electoral process.

A cog in the machine

Electronic voting is not a particularity of Brazil. According to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA International), based in Stockholm, Sweden, at least 46 countries already use electronic systems for capturing and counting votes. Of these, 16 adopt direct recording electronic voting machines. This means that they do not use paper ballots and thus register votes electronically, without any interaction with ballots.

But Brazil was one of its pioneers. In 1996, with help from the military, computer experts developed the country’s first electronic voting machine, introduced partly to combat fraud. The paper ballots system used until then were notoriously fraud-prone. Since then, each year the machines are adapted and improved to maintain the highest level of security.

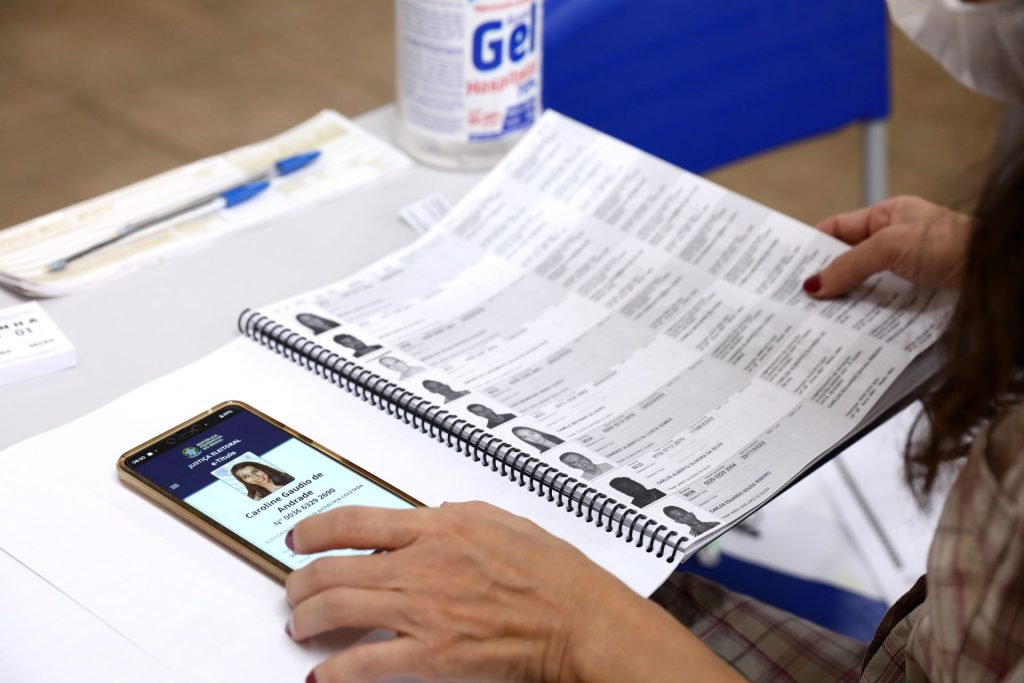

How does the Brazilian voting system works? de Amanda KasterLie in state

Although he defended electronic voting in 1993 when he was a federal deputy, since 2018 Bolsonaro made allegations that voting machines were prone to fraud, that despite his win, they were “easy to rig” by hackers and that he actually had won by a landslide in the first election round. By Brazilian laws, this would mean that he would have to achieve at least 50% + 1 of all valid votes (roughly 53,5 million), 4,25 million more than the polls showed.

Bolsonaro continued to claim he had been cheated even after he went on to win the presidential election by a sizable majority. Recently, Piauí Magazine compiled a video with all of the 181 weekly lives Bolsonaro did in his personal channel since 2019. In it, he has not been able to provide proof to back up his allegations, and has said as much:“There is no way to prove the elections were or weren’t fraudulent”, in july this year. However, both Bolsonaro and his supporters have continued to make claims about future fraud in the lead-up to the elections.

But what Bolsonaro gains

with these claims?

Behind the so-called concern to help the people, lies something more sinister, says Fernando Horta, professor in the Institute of International Studies of University of Brasilia (UnB), an specialist on theme and avid critic of the current government.

Raising the stakes

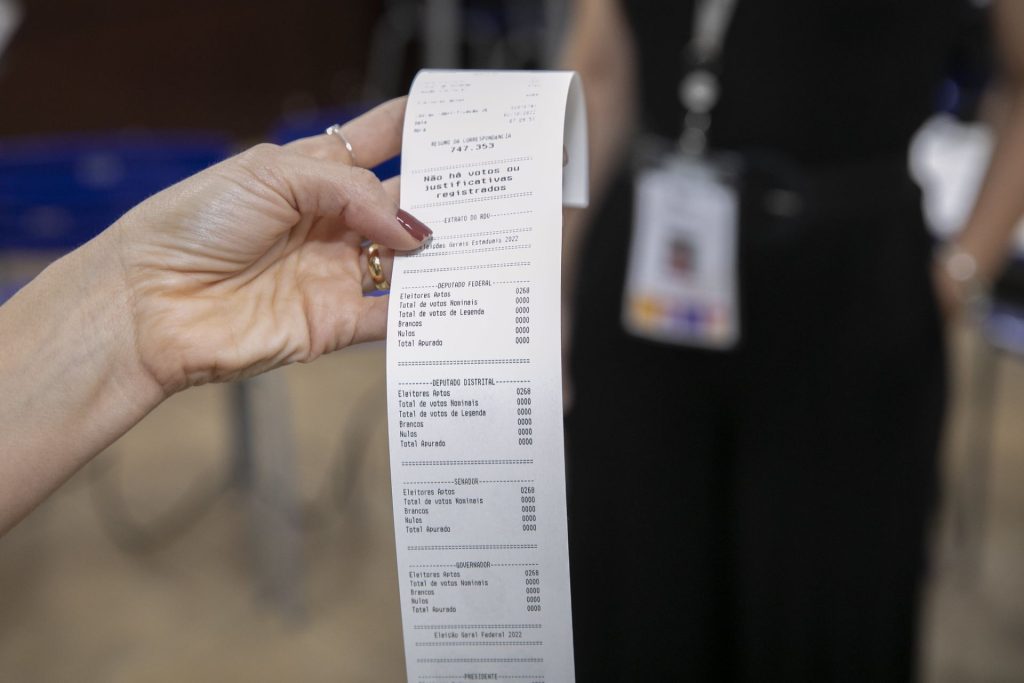

In the beginning of the electoral process, the participation of the armed forces was approved to help with the logistical process of carrying the electronic ballots, and to “guarantee the voting and counting” of the electoral process.The measure – which is customary in the Brazilian electoral system – was determined in a presidential decree published in the Official Gazette (DOU). However, when the internal reports of the first term made by the armed forces found nothing irregular, Bolsonaro had not authorized a public disclosure of their findings. Even then, the attacks continue to happen.

To most government’s critics, Bolsonaro may be laying the groundwork for an attempt to cling to power if the vote

doesn’t go his way. The last straw is to finally pass the law

to replace the current electronic voting system to give out

a paper receipt after the voting, a change that may seem

sensible to the population, but it actually undermines

all of the security process currently underway.

Looking at an overview of the newly elected Brazilian House of Representatives is not hard to see why:

Out of the ten most-voted parties 146 seats went to right-wingers (PP and PL), 154 to center-right (Republicanos, Podemos, União Brasil and PSD), 59 to the moderates (PDT and MDB) and only 82 to the center-left (PT and PSB). In the Senate, which also held elections this October to renovate a third of the senators, Bolsonaro’s PL won 14 seats out of 27, meaning now it holds the biggest electoral bench of the country. So big, in fact, that it holds the power to impeach and persecute judiciary ministers of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF). However, one thing is certain: “if Bolsonaro wins, this will be the last election with the electronic voting system as we know it, at least one without institutional interference since the dictatorship”, says Horta.

October 30th: one day. Two digits. In the end that’s all the Brazilians have to do to proceed with their election. The cost, however, might be much more than just numbers.